Follow the above link to see the presentation to the Atlanta Vietnam Veterans Business Association.

Follow the above link to see the presentation to the Atlanta Vietnam Veterans Business Association.

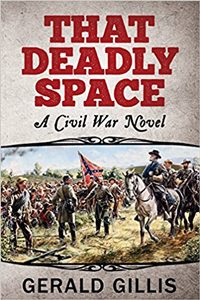

The third (and last) excerpt from my Civil War novel That Deadly Space.

On Tuesday, October 18, the Confederates broke camp and moved out after dark. They followed a narrow path between the Shenandoah River and the northern tip of Massanutten Mountain. They could move only in a single-file formation for long stretches, and thus could take no artillery with them. They met up with Masterson’s other divisions in the heavy fog and attacked the Federals in their campsite, achieving total surprise. Conor’s regiment led the attack from General Gordon’s Division, and they found many of the Yankee soldiers still half-dressed when they came out to meet their attackers. The Federal troops made a fighting withdrawal, but the Rebels won the field.

By 10:00 am, the Southerners had once again achieved what appeared to be a stunning victory.

The hungry troops stopped only briefly to pillage the Union supplies for all they could find. They had collected 1,300 prisoners and 24 cannons, but inexplicably the order to halt came just as they were readying to press the final assault. Conor immediately thought of the first day at Gettysburg where the order to halt had cost them dearly, and when he saw General Gordon ride into his position he, too, seemed perplexed.

“Why are we halting, sir?”

“Orders from General Masterson. I’m on my way to see him to discuss the matter. I want you to have your regiment ready to resume the attack, but in the meantime you are to halt in place. Do you understand?”

“Understood. We are halted, General.”

First Sergeant Tanneyhill came forward and handed Conor a biscuit and some bacon. “It’s still warm,” he said as he licked his fingers from his own unexpected but nonetheless much appreciated Yankee-style breakfast.

“We’re halting again at exactly the wrong time,” Conor said in disgust. “Courtesy of General Masterson.”

“Can General Gordon change his mind?”

“I doubt it. Just between us, General Masterson’s nothing but a hollow uniform. If you tapped him on the shoulder you’d probably hear an echo. And arguing with him is like picking up a dog with bowel complaint. It’s usually best just to leave it be.”

Tanneyhill laughed. “Why do you suppose General Masterson’s like that?”

Conor sighed. “That’s just who he is. The reason a skunk’s a skunk is because he has no sense of refinement. In the general’s case, he has no sense of battlefield refinement, so he panics and orders us to stop. It’s become a habit he can’t seem to break. Whenever he sees us about to become victorious, he slams the door shut and halts us in place. It’s like he’s satisfied with partial victory. I’m going to start referring to him as General Partial Victory Masterson. How do you like that, First Sergeant? Ole P.V. Masterson has halted us again. What a surprise.”

“You might want to lower your voice, sir.”

“Yessir, ole P.V.’s gonna get us in position to partially win this damn war. And then he can go back to his partial home with his partial family and find some partial job and live the good partial life. And when he grows old he’ll probably figure out a way to partially die.”

“Sir, my advice to you is to lower your voice.”

“Okay, I’ll split the difference with you and partially lower my voice. Besides, what’s ole P.V. gonna do about it if he hears me? Order me to pack my gear and send my insubordinate ass to the Shenandoah as punishment? Well guess what? It appears he’s already done that.”

Conor then turned his attention to the food and consumed it in two large bites. When a lieutenant courier showed up on horseback and told him to halt his regiment in place, per General Masterson’s orders, Conor began gesturing and cursing so vehemently with a mouth so overstuffed that white bits of biscuit were sent flying.

The lieutenant could see Conor’s red-faced agitation but could understand nothing that was being said.

“He’s aware of that order, sir,” Tanneyhill calmly told the courier who immediately turned about and galloped away, but not without looking back.

“What’s the matter with finishing what we started?” Conor said to no one in particular. “Have we lost our nerve in partial victory as well as defeat?”

Tanneyhill stepped beside Conor, put his hand on his shoulder, and said in a calm, measured tone, “Easy does it, sir. This regiment doesn’t need you serving time in a military brig for insubordination. It needs you out here in command. You’ve made your point, so let it be. Please, sir, no more.”

Conor took in a deep breath and let the matter pass. After a few minutes he was greatly ashamed at his lack of maturity, and he thanked Tanneyhill for the abundance of his.

The Confederates pressed forward, but only after several hours had passed. The Federals resisted stiffly and the Rebels withdrew without much of a determined attack. The main Federal counterattack came at about 4:00 pm, with Sheridan’s cavalry attacking the Confederate flanks and his divisions pressing against the Reb center. For an hour, both armies battled furiously north of Middletown, but then Masterson’s left flank began to crumble and Union cavalry suddenly appeared in the rear of the Confederates. More of the gray army collapsed when the men realized that the Federal cavalry might block their path to Cedar Creek, their only avenue of escape. Rebel artillery delayed the Union advance, but only for a short interval. To make matters worse, a small bridge on the Valley Pike collapsed and made it impossible for the Confederates to cross a creek south of Strasburg with their wagons, including the captured artillery. Thus, they had no choice but to abandon the guns and the wagons.

As the retreat was underway, Conor noticed a Confederate major on horseback, from General Masterson’s staff, frantically waving his sabre at a group of Conor’s soldiers. The officer was threatening to slash a frightened private when Conor rushed to confront the major.

“Put that sabre away, you damned fool,” Conor shouted. “If you can’t use it on the Yankees, then give it to someone who will.”

“These men are cowards,” the major shouted in return. “They should be punished. General Masterson will be interested to know how your troops behaved in battle today, sir.”

“Then go back and tell General Masterson to punish all of us since it’s his entire army being routed from the field. What does that tell you about his leadership?”

“It’s not his leadership, sir. It’s a failure of execution on your part. What would that tell him about you?”

“General Masterson and his entire staff, including you, you dandy pompous ass, should be relieved of duty twice—once for incompetence and another for being too damn dense to know it.”

“You are very badly mistaken, sir.”

“No, sadly, I am not mistaken. And let me add one other thing: You threaten another of my men on this or any other battlefield and I will personally blow a very large hole in that thick but otherwise empty skull of yours. Now get the hell out of my sight. Go!”

The officer stared at Conor, but made no move. Conor quickly drew and cocked his pistol and then took aim. The wide-eyed major spurred his horse and sped away. First Sergeant Tanneyhill, who had observed the entire scene, shook his head but remained silent.

Excerpted from That Deadly Space depicting wounded patient Conor Rafferty’s confrontation with a fellow patient in Richmond’s Chimborazo Hospital.

After his daily session of walking around the hospital grounds for nearly an hour to build his endurance, Conor heard the sudden piercing scream of a nurse as he came back to his ward. There, a truculent young patient from another ward was holding a surgeon’s scalpel to the throat of a doctor who had been attending to an amputee. The startled nurse stood nearby, her hands over her mouth, fighting back tears of fright and panic.

“They’re trying to kill me, so I’ll kill them instead,” the wild-eyed, gaunt, shaggy bearded man shouted.

The middle-aged doctor tried to remain calm, but the prospect of having his throat slit was making it difficult.

“They don’t think I know what they’re planning for me. The voices tell me. The voices tell me everything. They want to kill me, to get rid of me. And I won’t let them.”

The other patients in the ward watched but said nothing.

“Put the scalpel down, sir,” Conor called forcefully, approaching to within fifteen feet. “Let the doctor go and put the scalpel on the ground.”

“Who the hell are you?” the man said, his expression hard and threatening. “And try to take another step toward me and this here doctor will be dead before your foot hits the ground.”

Conor stopped, noticing the additional pressure applied to the doctor’s throat.

“Are you a soldier? Where did you serve? Were you in the battle at Manassas like I was?” Conor asked, softening his tone.

“Ain’t none of your business. I’m here to get even with these doctors.”

“Forget the doctor. Tell me about where you served. Were you there at Manassas like I was? Now that was one hell of a fight, wasn’t it? I’ll bet you were there. Am I correct?”

After a long pause, the man eased his grip slightly. “I was there. C Company, Second South Carolina. Captain Dan Remington was my commanding officer. Who were you with?”

“B Company, Seventh Georgia,” Conor answered. “What’s your name, soldier?”

“Grimes. Private Eric Grimes. This doctor here knows all about me. And he and his fellow butchers are trying to kill me. But today they’ll lose and I’ll win. It’s a war with them. It’s nothing but a damn war.”

“Put down the scalpel, Eric. These doctors are not here to hurt you or kill you. They are trained to heal, not harm. And besides that, they’re on our side.”

“How the hell do you know that? Who are you, anyway?”

“I’m Captain Rafferty. We fought together at Manassas, you and I, on the same field. And you and I helped win a great victory that day. Put down the scalpel, Eric. You’re a soldier. You don’t hurt innocent people. That is your duty. This doctor is helping lots of soldiers here. That is his duty. You hurt him and we’ll lose someone who is helping us, who is helping our fellow soldiers, and who won’t be around to help those who will be coming here after us. Now put down the scalpel.”

Two sergeants from a security detail, their pistols drawn and cocked, suddenly entered the ward, walking slowly and deliberately toward the scene.

“Tell those people to stay put, Captain, or I’ll kill the doctor. Tell ‘em I’ll do it.”

Conor turned and caught the attention of the two men. “Don’t come any closer,” he said in a calm, steady voice. “This is Captain Rafferty, and I’m ordering you to stay where you are and hold your fire.”

“We’ve been ordered to stop this man and take him into custody, Captain.”

“I’ve just put a hold on those orders for now. Stay where you are.”

Conor then turned to Grimes. “There, Eric. They’ve stopped. Nobody’s going to hurt you. I’m coming over there and I want you to hand me the scalpel.”

The doctor’s eyes bulged. Grimes stared at Conor but said nothing.

“You and I fought together, Eric. You’re a soldier in a hospital, and I’m asking you as a fellow soldier to release the doctor, let him go home to his family tonight. If your mom were here, she would be saying the same thing. She would be telling you not to hurt anyone. Captain Remington would tell you the exact same thing. He would never want to hear about one of his C Company soldiers hurting an innocent man. Now give me the scalpel.”

Conor took a step toward Grimes, then another.

“That’s far enough, Captain,” Grimes said as he released his hold on the doctor and shoved him away. “Go on, doc. Go on home to your family.”

Grimes then plopped down on the floor and burst into tears, the scalpel still in his hand. The two soldiers promptly rushed Grimes, their pistols aimed at Grimes’ head.

“No, don’t shoot him,” Conor called loudly.

“He’s a crazy man,” said one of the sergeants. “He’s a danger to everyone here.”

“He’s a soldier, not a mad dog,” Conor countered. “I’m ordering you, do not shoot him.”

Conor calmly walked to Grimes’ side and took the scalpel from his trembling hand, then patted him softly on the shoulder. Grimes looked up, his eyes wet with tears, a pleading expression on his face.

“I want to go home, Captain. Please tell them to just let me go home.”

More soldiers from the security detail arrived. They brought Grimes to his feet, tied his hands behind him, and quickly whisked him from the ward.

The still-shaken doctor returned soon thereafter and thanked Conor.

Nothing further was ever heard about Eric Grimes.

Excerpted from That Deadly Space, depicting an event near the end of the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg:

“Sir, they’s Yankee snipers all up in them houses yonder. We’ve had three men shot at in the last half-hour.”

“I need to get a look at Cemetery Hill. What do you suggest?”

“That thing’s crawling with Yankees, sir. Listen and you can hear ‘em diggin’ in up there.”

“I need to do more than hear them, Corporal. Is there a house close by that has a rooftop I could get on?”

The corporal pointed to a house across the street. “I’ve got a sniper on the roof of that house right there. A good bit of Cemetery Hill’s in view from up there. Follow me, Major.”

Conor tied Shannon to a post outside the two-story home and followed the corporal inside. There were at least a dozen wounded soldiers from both sides being treated by several women. He stepped around and over them and followed the corporal to a staircase that led to the roof. The sniper on the roof glanced at Conor but otherwise kept his eyes ahead in search of targets.

“Might wanna scrunch over, sir. Don’t make yourself—“

The Confederate sniper suddenly fired at an opposing shooter on a rooftop across the street, perhaps seventy-five yards distant. The Yankee soldier slumped forward and dropped his rifle, his arms dangling and his body nearly tumbling off the roof. Blood began streaming down the side of the house.

“Good ‘un, James,” the corporal said. “I’ll bet that’s the same sumbitch tried to pop ole Red while ago.”

Conor scrunched over.

As he looked through his field glasses in the fading light, Conor could see the Federal soldiers who had been running for their lives earlier in the day now furiously digging holes and piling rocks and fence rails in front of their positions. A tall, imposing officer on horseback moved about the men in a calm, deliberate manner, giving orders to other officers, occasionally personally directing the placement of cannons or troops. He would sometimes stop and say something that would cause a group of soldiers to laugh in that particularly loud, rowdy way that soldiers cackle at lewd comments. It was clear that these men had retreated as far as they intended, and they were now preparing a defensive position that would take an exacting toll on any attacker. Conor made a sketch of what he could see and an estimate of the number of Federal soldiers he thought were occupying the hill. He then got up to leave the rooftop.

The corporal noticed the missing little finger on Conor’s writing hand. “Yankee ball take off that finger, sir?”

“Yep. I suppose it’s still out there somewhere on that sunken road at Sharpsburg.”

“We was both there,” the corporal proudly announced with a point toward his sniper buddy. “Now that was a fight.”

“You goin’ up that hill, Major?” the young sniper asked Conor as he was leaving.

“I think so,” he answered. “Better now than later.”

He gave a reluctant nod. “Good luck, whenever you do.”

There was an attractive young woman on the second floor of the house who was leaning back and resting in a chair when Conor came back inside. She appeared to be about his age, with blond hair and blue eyes, of medium height and build. She glanced up at Conor with a tired expression as he approached. When she saw his uniform, she quickly avoided eye contact.

“Do you live here, ma’am?” Conor asked.

“It’s my mother’s house, but I live here, yes,” she replied, still without looking at Conor.

“This has been some day, huh?”

She frowned, but said nothing.

Conor reached an outstretched hand toward her. “I’m Major Conor Rafferty.”

She hesitated a moment, staring at his hand and then noticing the missing finger. She soon relented and gave him a firm handshake, finally making eye contact. “Amanda Wiedenour.”

“Thank you for looking after these wounded men, Amanda. I was injured at Sharpsburg and I’ll always appreciate the help I was given in the home of a private citizen.”

“I would have much preferred that you and your soldiers had never come to our peaceful little town. Things will never be the same for us now. This is going to become nothing but a disaster, a disaster on a huge scale, thanks to you,” she said, her voice breaking. “My brother’s out there somewhere, and this man you’ve got on our roof could be aiming his gun at him, for all I know.”

“My brother’s out there somewhere too, Amanda. I’m sorry you and your mother had to be pulled into this. I truly am.”

“I’m sorry any of us in Gettysburg had to be pulled into this,” she said, her tears streaming down her cheek.

Conor attempted to change the subject. “What do you do when there’s not a war going on in the middle of your town?”

She looked at him in disgust.

“Yes, you’re right. Those were poorly chosen words. I apologize, ma’am. I promise you I didn’t mean that to be as callous as it sounded. Please forgive my rather clumsy attempt at humor.”

She looked away.

“Let me try again. What do you do to make a living?”

“I’m a seamstress,” she said, wiping her eyes with the bottom of her apron.

“Ah,” he said. “I’m sure you’re a good one.”

“I am a good one. Are you good at what you do?”

“Well, I try to be. I had expected to become a lawyer but things obviously changed for me, as they did for most of us. I’ve spent nearly six months recovering in hospitals since I joined the army, so the lawyering way of life has an even greater appeal to me now.”

She laughed out loud but quickly caught herself, cleared her throat, and resumed her rigid demeanor. “What were you doing on our roof?”

“Looking for a good restaurant. I haven’t eaten in days, it seems.”

“I believe that, sure.”

“Of course you do.”

“Did you see what you went up there to see?”

“I think we should talk about other things, ma’am.”

“Like what? Like how much we’re all enjoying our daily lives here in Gettysburg since your army showed up?”

“That wouldn’t be at the top of the list of the things I’d care to talk about. Maybe I should just leave.”

She took a deep breath. “So where is your home?”

“Georgia, near Atlanta. I haven’t been home in two years.”

“That’s a long time,” she said softly. “Did you leave a girl behind?”

“Well, not really,” Conor said with a chuckle.

“Is she pretty?”

“Uh, yes, very. Her name is Patricia Welch. She’s a schoolteacher.”

“So what happened?”

“She wanted to get married, and honestly I was just about to propose, I really was. But then the war started and I cooled on the idea.”

“So you just up and left?”

“Pretty much, yeah,” Conor said with a chuckle as he remembered his conversation with Rebecca Gordon in Richmond.

“Boy, you’re a real prize.”

“I know. I’m not sure anyone will ever have me now.”

“Oh, I’m sure you could have your pick of those pretty Southern belles,” she said in an exaggerated accent.

Conor smiled. “What about you? Are you married or spoken for?”

“No, neither. That is probably the only thing we have in common, but not for the same reasons. Your Rebel army at Fredericksburg, Virginia killed my boyfriend. We were making plans for after the war.”

“I’m very sorry.”

She gave him a hard stare.

Conor again decided to change the subject. “Our regular soldiers who are coming into your home, like the men on the roof, are they being respectful?”

She shrugged. “They’re polite, yeah. But I’d rather not have them here at all if you want to know the truth about it.”

“I understand. They’re just doing what they’re told, Amanda, like the rest of us.”

“Then tell them to go someplace else.”

“I’m sorry, but I can’t do that.”

She sighed. “I just hope this whole nightmare ends soon.”

Conor nodded. “We agree on that. Well, I really should go now.”

She looked at him with reddened eyes and said, “Yes, you probably should.”

Conor turned to leave but then stopped and asked, “Do you have enough food and water?”

“No,” she answered quickly. “We’ll be out of both soon. And we need bandages. We’ve used up all the sheets in the house. But we’re really starting to feel desperate about the food and water. Please, help us if you can.”

“I’ll see to it right away. I can’t promise anything, but I’ll do what I can.”

Conor held out his hand again and she took it.

“God bless you, Amanda Wiedenour.”

Conor walked down the stairs and back through the open part of the house where the wounded were lying. He stopped and spoke briefly to the three wounded Confederates, all of whom were conscious and aware, and then started toward the door.

“Major?” she called from the top of the stairs.

He turned and heard Amanda say, “Please don’t forget about the food and water.”

Alexander “Sandy” Bonnyman Jr was born in Atlanta, GA on May 2, 1910 before moving to Knoxville, TN in his youth. During World War II, Bonnyman enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps at age 32 and underwent recruit training at Marine Corps Recruit Depot, San Diego, CA. He could have exempted military service by virtue of his owning and managing a copper-mining business deemed strategically important to the war effort. But he chose to serve instead.

As a result of his exemplary leadership as a combat engineer during the Battle of Guadalcanal in 1942, Bonnyman was awarded a battlefield commission as a Second Lieutenant. It was during the November 1943 Battle of Tarawa that Bonnyman’s extraordinary leadership skills were once again displayed. On the battle’s first day and upon his own initiative, he voluntarily led a group of Marines in silencing an enemy installation while other Marines were pinned down on the beach. His primary duties as a beachhead logistics officer required no such risky activity in the face of the enemy. But he chose to lead instead.

On the battle’s second day, and once again exercising exceptional initiative, Bonnyman patched together a group of 21 Marines and attacked a reinforced enemy shelter. While the initial attempt met with limited success, Bonnyman and his Marines had to withdraw to take on more ammunition and explosives. The second attempt flushed large numbers of enemy from the position where they were quickly dispatched by Marine infantry and a supporting tank. Bonnyman was shot and killed while pressing the assault from a forward position in what became the attack’s final phase. When leaders were desperately needed in a desperate fight, he again chose to step forward and lead.

He was interred with other Marines in an impromptu burial trench whose location was inadvertently lost by the end of the war.

Lt. Alexander Bonnyman was later awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor for his actions at Tarawa. His “dauntless fighting spirit, unrelenting aggressiveness and forceful leadership” were cited in the award.

In March 2015, the lost burial trench was located by History Flight, Inc., a Florida-based nonprofit that has recovered more than seventy sets of Marine remains from Tarawa. In May 2015, some seven decades after his death in battle, Lt. Bonnyman’s remains were found and thereafter positively identified. What made the discovery all the more poignant was that Clay Bonnyman Evans, the grandson of Lt. Alexander Bonnyman, had volunteered to travel to Tarawa to assist in the search. Evans was on the scene when his grandfather’s remains were unearthed.

In September 2015, Lt. Bonnyman’s remains were returned to his childhood home in Knoxville, TN. He was buried with full military honors at Berry Highland Memorial Cemetery. He was home, finally.

Semper Fi, Alexander Bonnyman. And welcome home, sir.

General John Reynolds, one of the Union Army’s most respected commanders during the Civil War, might have played an even larger role in American history if not for his death during the opening hours of the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863.

John Reynolds was a native of Lancaster, PA and an 1841 graduate of West Point. During the Mexican War, Reynolds became friends with Winfield Scott Hancock and Lewis Armistead, two career U.S. Army officers who would eventually oppose one another during Pickett’s Charge on July 3, 1863 at Gettysburg. Armistead would die leading a Confederate brigade opposed by the Union soldiers commanded by his friend Hancock. The fate of the three close friends was sealed during the three-day battle: Reynolds and Armistead would be killed in action, and Hancock would be seriously wounded.

Earlier in the war, an embarrassed Reynolds had been captured by Confederate forces and taken to Libby Prison, where he was quickly exchanged. He later served at the battles of Second Bull Run, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville. To the surprise of many senior Union officers, Abraham Lincoln selected George Meade to replace Joseph Hooker as commander of the Army of the Potomac on June 28, 1863. John Reynolds, thought by many at the time to be the finest commander in the U.S. Army, would have been the more logical (and popular) choice.

On July 1, 1863, Union cavalry commander General John Buford established defensive lines to the north and west of Gettysburg. Elements of Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia were concentrating at Gettysburg at a faster rate than those of the Union, and Buford’s modest forces quickly became outnumbered. The lead division of John Reynolds’ I Corps began arriving in time enough to reinforce Buford’s cavalrymen, to Buford’s immense relief. In ratifying Buford’s defensive plan and then deploying his I Corps units against the Confederates, Reynolds essentially committed the Army of the Potomac to what would become a massive pitched battle at Gettysburg. While personally directing the men of the Second Wisconsin, Reynolds called, “Forward, men! For God’s sake forward!” He was then shot in the back of the head and died immediately. He was the highest-ranking officer of either army to die on the field at Gettysburg.

Acclaimed author Jeff Shaara brings up an interesting supposition. Had John Reynolds lived and been given overall command of the Army of the Potomac, and had Reynolds pursued Lee after Gettysburg and destroyed his army before it could reach Virginia, what historical implications might have resulted? Lincoln may not have needed the services of Ulysses S. Grant after all. A victorious Union, under the able command of John Reynolds, might have altered the course of American history. Given America’s penchant for elevating its military heroes to high office, might Reynolds, and not Grant, then been elected president?

A unique and compelling character, John Brown Gordon was one of Georgia’s most consequential political and military leaders of the nineteenth century. He studied at the University of Georgia, though he dropped out shortly before graduation to read law. He possessed no formal military training, yet he rapidly ascended through the officer ranks of the Confederate army to where, by the end of the war, he commanded a corps in Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

Apart from the protagonist in my Civil War historical novel That Deadly Space, John B. Gordon’s role is one of unequalled importance. His fictionalized involvement in the novel is that of a mentor to, and the commander of, the central character Conor Rafferty. Conor serves with John Gordon in the battles at Antietam, Gettysburg, The Wilderness, Petersburg, and at the close of the war near Appomattox Court House.

What made John Gordon so unique? For starters, he was a gifted military commander with astonishing bravery.

At Antietam, the audacious Gordon led his regiment in the desperate struggle at an old eroded farming road that would thereafter be referred to as Bloody Lane. He was shot twice in the same leg, once in the arm, then the shoulder, and finally in the face. He was eventually nursed back to health due in large measure to the efforts of his wife, who travelled with him throughout the war.

During the Confederate invasion of Pennsylvania, Gordon’s brigade occupied Wrightsville, on the Susquehanna River. When Union militia burned the long covered bridge spanning the river to thwart Gordon’s crossing, embers from the fire quickly spread to Wrightsville. Gordon formed his Confederate troops into a bucket brigade and managed to prevent the fire from destroying much of the town.

At the war’s end, as the defeated Confederate soldiers were turning in their muskets and other associated military equipment, Union General Joshua Chamberlain, who earned the Medal of Honor at Gettysburg, called for his men to salute their conquered foe. Seeing Chamberlain’s salute, Gordon sat upon his horse, drew his sabre, and returned Chamberlain’s salute. It was an impressive display of mutual respect that would never be forgotten by either general, nor by those who close enough to witness it.

After the war, John B. Gordon served as a United States Senator and later as Governor of Georgia. Gordon opposed Reconstruction, and was thought to be the titular head of the Ku Klux Klan though his role there was never conclusively determined. However, as a politician he shaped a vision of national unification, an economic vitality of a South free of slavery, and care for veterans. He died in 1904 at the age of 71 and was buried in Atlanta’s Oakland Cemetery. A crowd estimated at 75,000 attended the service.

A man of many talents, John B. Gordon was indeed a unique and consequential figure of his time.

It’s a Gold Medal for That Deadly Space! Heartfelt thanks to the Military Writers Society of America for their selection of my Civil War novel for their Gold Medal award. I am grateful to MWSA for their selection of my book for this prestigious award. You might notice a second Gold Medal in the picture. The first was awarded in 2011 for my historical novel Shall Never See So Much. I’m deeply honored to be a two-time recipient. I might add that Michael Phelps, with his 23 Olympic Gold Medals, has little to worry about.

Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines offended as: to cause (a person or group) to feel hurt, angry, or upset by something said or done.

There is a seemingly endless number of people these days who seem to live in a perpetual state of being offended. It must be exhausting. And burdensome. If there are words spoken or actions taken that can be termed as offensive, real or imagined, there is someone somewhere all too willing to take on that burden. Some of the offending causes are petty and laughable; some are legit. Some have resulted in Occupy Wall Street, overt thuggery aimed at Trump supporters, and now Antifa, all courtesy of the hard political left. Now, from the hard right we have white supremists and Neo-Nazis. Can’t we all get along here in our respective offended conditions?

Many soft-shelled college students are offended by the scheduled appearance of a conservative speaker on campus, and thereby insist that the speaker be turned away. Feckless college administrators have a long and shameful history of bending to the demands of loud students. Leaking a steady stream of pee and heading for the exits at the first sign of distress, many of these administrators ignore not just the tenets of free speech, but a worthwhile teaching opportunity as well.

Politicians are hardly any better. Some of the most prominent elected officials of the past decade have chosen to avoid naming the very enemy who is intent upon destroying this nation. Why? So as not to offend them, as if that would somehow make radical Islamists less inclined to murder our citizens, blow up our soldiers, and crash airliners into our buildings. Is it possible to defeat an enemy without offending them? It hasn’t worked thus far.

The recent spectacle in Charlottesville was alarming on several fronts. Seeing groups of Americans on the verge of killing one another is unsettling, to say the least. Just how much the issue of the Confederate monuments factored into the confrontation is still unclear to me, but what is clear is that some were offended by their existence and others by their removal. The cynic in me says that many of the agitators with clubs in hand were there only to bash some heads, unlikely as they were say, two years ago, to even know who fought whom in the Civil War. Or any other American war fought since.

ESPN saw fit this week to pull an Asian-American sports announcer named Robert Lee from his broadcast duties for the upcoming University of Virginia football game on September 2. ESPN stated that, among other things, they were concerned about Mr. Lee’s safety given the recent event at Charlottesville.

Has the act of being offended become such a fashion that virtually nothing is so small and insignificant that it can’t be found to be offensive? It would seem so, from Halloween costumes to silly jokes to Confederate (and soon other) monuments.

Or is it contagion? Again, it would seem so. Creating safe spaces on campuses doesn’t mean hardened bomb shelters. It means protecting students from ideas and speech that make them uncomfortable. This can, and likely already is, creating a level of intolerance in those who demand a sheltered existence.

Or is it admonition? If an innocent man cannot do his job for fear that his name will offend someone—his name!—and perhaps risk his safety as a result, well, this is a sign that the entire matter of being offended is potentially becoming far more dark and sinister.

It’s not a pretty picture. This nation has survived horrifically destructive wars, a Great Depression, a Great Recession, and 9/11. Can it survive the present dangers with some of its populace in safe spaces while others attack each other in the streets?

Good question, huh?