Today, November 10, 2022, is the 247th birthday of the U.S. Marine Corps. All across the globe, active-duty Marines will take time to pay homage to their Corps, to its extraordinarily rich heritage, and to all of those who have gone before them, remembering especially those who have been wounded or killed in battle defending this nation. At most Marine posts, there will be a cake, a toast or two, and a reminder that the Marine Corps is an organization committed to excellence, to unselfish service, and, most importantly, to winning.

This Marine Corps Birthday, I’d like to celebrate the life of Vince Dooley, the longtime football coach and athletics director at the University of Georgia, who died on October 28, 2022. Coach Dooley had been a Marine Corps officer in the mid-1950s, and his pride in his service in the Marines was evident to all who knew him. Dooley’s Georgia Bulldogs football teams were known for their toughness and their ability to battle and overcome—traits that reflected the character of their former-Marine leader. During his 25-year tenure as head coach, Dooley’s teams won 201 games, including six Southeastern Conference championships and one national championship. At the time of his retirement from coaching in 1988, only Alabama’s Bear Bryant exceeded Dooley in wins among SEC coaches.

In a small sampling of his many honors, Dooley was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame as well as the Marine Corps Sports Hall of Fame. From becoming a head coach at UGA in 1964 at the age of 31, until his death last month at age 90, Dooley became a revered figure at UGA and across the State of Georgia, not solely for his gridiron success, but also for his kindness, his integrity, and his loyalty. He will long be remembered as a focused, intelligent, highly successful man of many accomplishments, but who always remained approachable and gracious.

I had some history with Coach Dooley. He became a role model for me when I was seventeen years old. I admired him from afar for the immediate success he had in turning around what had become a moribund football program at Georgia. When soon thereafter I became a student at UGA, I could judge by the esteem he held among his football players that he was indeed the real deal. After I graduated from college and became an officer in the Marine Corps, Coach Dooley and I exchanged letters, a habit we would keep up intermittently for the rest of his life. Every time one of the four novels I have written was released, I would always make sure Coach got a copy hot off the press. He was always pleased to receive the book and generous with his comments.

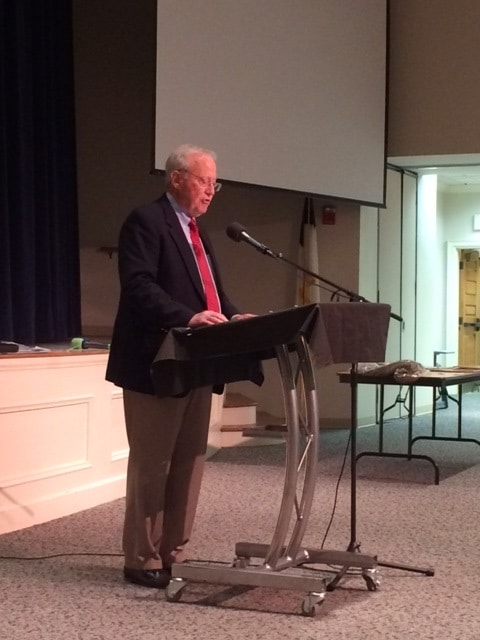

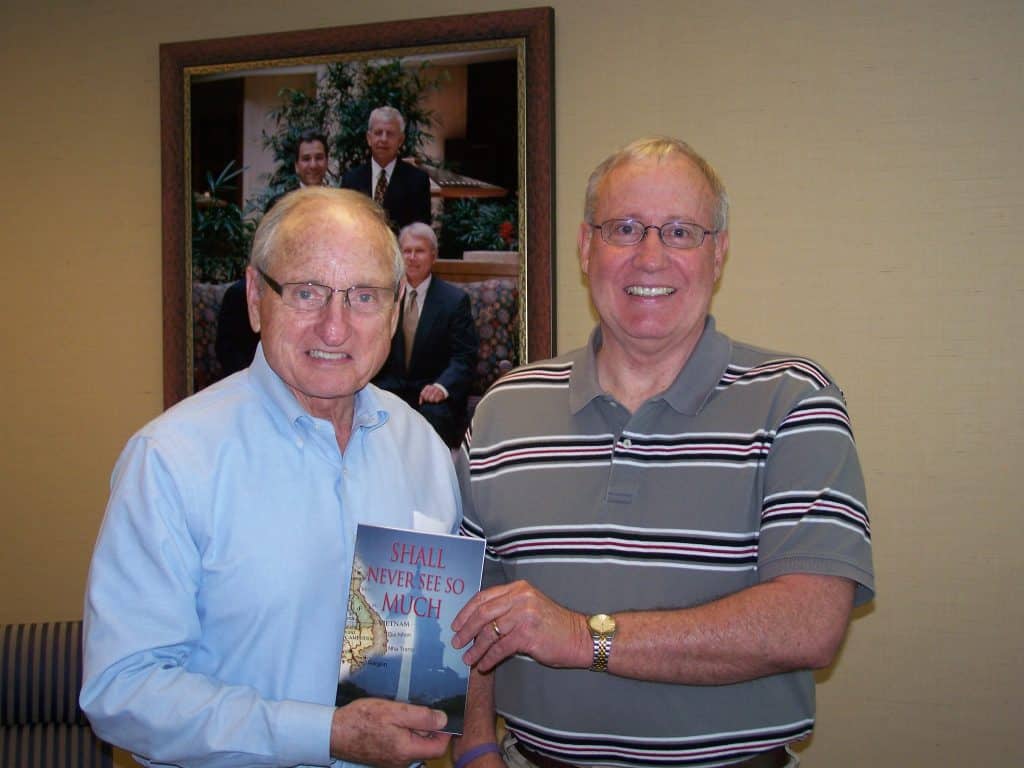

He was also generous with his time. My wife and I had a chance to meet with him when he was consulting with Kennesaw State University over their ambition to start a football program. We met in a private office near the university and talked about football, the Marine Corps, and gardening which had a special attraction to him given the world-class garden he maintained at his Athens residence. I signed my latest book and gave him a copy. He signed a picture for me. We took a photograph together. He was in no hurry to conclude our session, but then again, I realized he was being paid for his time as a consultant, so I thanked him for all he had meant to me and so many others he had touched with his extraordinary accomplishments.

This Marine Corps Birthday I will think of Coach Dooley. One of the highest compliments I was paid during my business career was when a colleague referred to me as our company’s version of Vince Dooley—always calm and collected but always well prepared to take on and beat the competition. I’ll always cherish that compliment, even though I clearly knew that I could hardly compare to such a giant of a figure. Still, I was grateful that my colleague compared me to Coach Dooley rather than, say, Dog the Bounty Hunter, or some such. That would have been far less pleasing (and highly unlikely to have found its way in this or any other post).

Much like the Marine Corps he served with such pride, Vince Dooley knew how to lead, and especially how to win. He sought excellence in everything he did. He served his Bulldog football players with great loyalty and devotion, teaching them life lessons along the way that benefited so many. He donated his time to many charitable organizations, using his considerable celebrity in service to others. And he was an inspiration to countless individuals like myself who will be forever thankful for the example he provided. His was a life exceedingly well lived.

Thank you, Coach Dooley. And Semper Fi.

Happy Birthday, Marines.